Hello, and welcome!

Among other things, this blog is a dive into two foundational texts of modern Neuroscience: William James’ “Principles of Psychology” (1890), and Santiago Ramon y Cajal’s “Texture of the Nervous System” (Published in three volumes, from 1899-1904). I’ll fork off into other things Neuro so there’s some variety in our diet, and so we can occasionally slip back into the twenty-first century, but really, the idea here is simple, perhaps to the point of bone-headedness. We’ll start with page one of both books, and alternate between them a chapter at a time, until, after having read about as many pages as Don Quixote, the Bible, and War and Peace combined, we’re done. We won’t be lacking for things to ponder, and I hope to convince you along the way that these texts are the basic play book for modern Neuroscience. They have almost all the big ideas in gestational form, and ask all the urgent and enduring questions. But more importantly: they are moving, intimate, and large-hearted. They’ll change the way you think about life.

Why am I doing this, and why meditate on some dusty old texts rather than simply showcase the latest greatest neuroscience? It’s an experiment, obviously, but my working conjecture is this: they offer an unusually deep and relatable way to contemplate the mind and brain, and one that makes for an inviting public conversation. They give us an excuse to approach the brain with “beginner’s mind”, to truly see the garden before the things in the garden were named. On a more practical note, I hope to leave a useful artifact for the field, and to use this as a way to break some of my bad writing habits that I’ve found to be really limiting (obsessive re-reading, rumination to the point of paralysis, etc…)

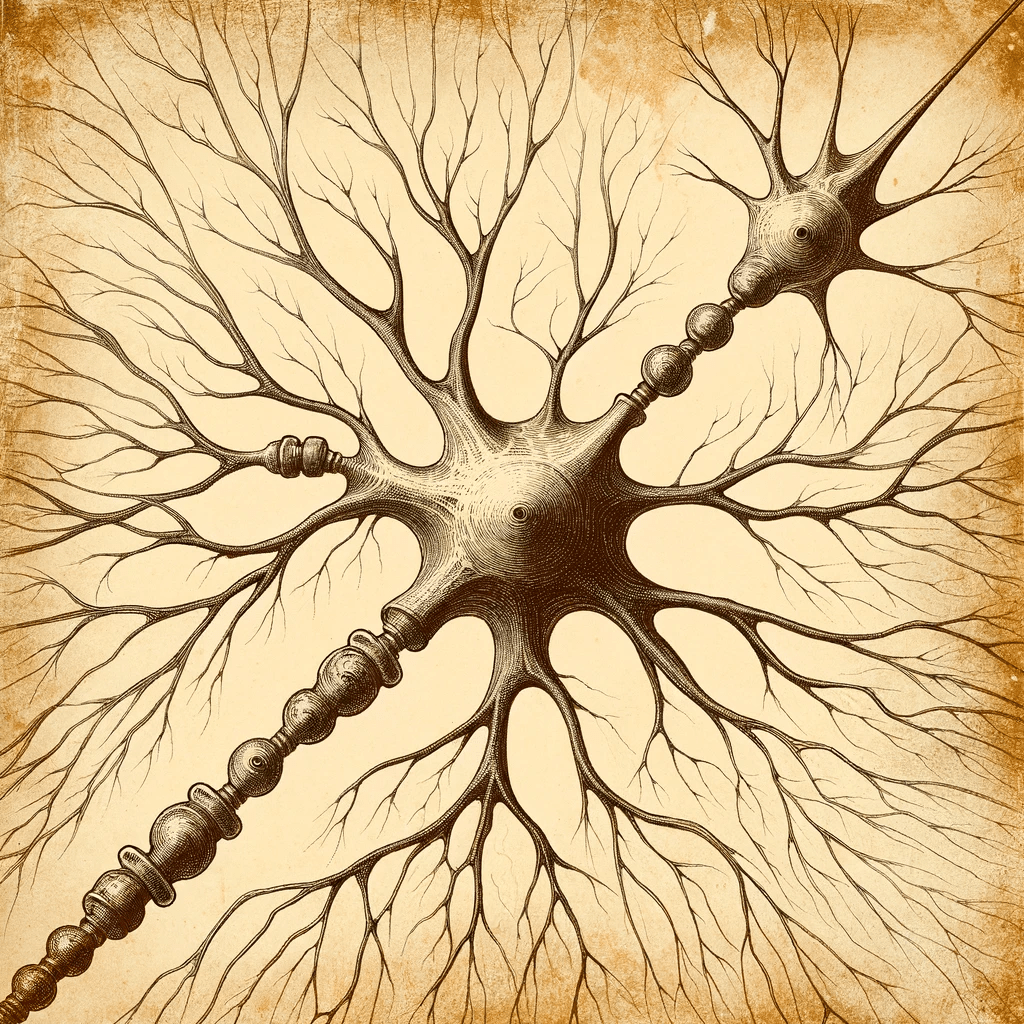

I think there are two main reasons why James and Cajal remain not just relevant in some “respect your elders” sort of way, but are actually still fresh, and I’ll start with the more formal and less sentimental one first. Basically, they offer the clearest, deepest, and most passionate statement of two fundamental principles of modern neuroscience: the neuron doctrine, and the idea of functionalism. There were plenty of other contributors to these ideas, and J&C stood on the shoulders of many giants, to be sure, but they really are remarkable for their persuasiveness, as well as the clarity and durability of their writing (and drawing, in the case of Cajal). The neuron doctrine (Cajal’s contribution) is the idea that neurons (brain cells) are discrete cells just like any other in the body, from which circuits and systems are composed, and whose activity explains our behavior. Functionalism (James) is not so much a single idea with a clear progenitor as it is a philosophical commitment. And that commitment is something like: “Minds exist for reasons, and these reasons are not miraculous.” Functionalism rejects notions that smack of ‘inner lights’ and ‘mental essences’ that act outside the scope of physical law, and which serve transcendent ends. In their place, it gives us brains subject to material constraints, shaped by struggle, striving, and accident. Marry these two sets of ideas, and you have what you can think of as the mantra of modern neuroscience: we don’t have minds for the purpose of having some luxuriant inner theater (though having this is one hell of a side effect!). Rather, we have minds because the real world presents real problems to solve. And the solutions to these problems can be thought of as stories that are composed slowly, over eons, by hook or by crook, with slender, spindly neurons as the protagonists.

“Better live on the ragged edge, better gnaw the file forever!”

William James, The Principles of Psychology

If that was all you knew about James and Cajal, it could be easy to imagine them as arch materialists, looking to rain on the humanists’ parade and assure us that for all our art and striving we’re nothing but a few kilos of prime rib trying to stay fresh for another day. Reading them like that would be to miss them utterly, though, and that brings me to my second, more sentimental proposal for their relevance. In their writings, they wanted to articulate a scientific aesthetic that respects the mysterious, and has awe and humility before it. Yes, they thought in terms of mechanism and physical law, but they also thought that human struggle and fulfillment were real and meaningful, and as much a part of nature as cells or atoms. Interestingly, both scientists started life as aspiring artists, and were quite gifted. Cajal’s conception of the single neuron was an ode to the individual’s powers of self-determination, and he fought for and protected this idea to the point of mania, likening himself to a knight (literally) called to battle when the idea was challenged. James, in The Principles, urges us to not accept easy answers to the mind-body problem, whether offered by mysterians who declare it beyond human comprehension, or over-confident scientists who glibly call it a non-issue. “Better live on the ragged edge,” he says. “Better gnaw the file forever!”

In his book on William James, the late cultural historian and critic Jacques Barzun described The Principles as a literary masterpiece, not just a masterpiece of scientific exposition. “I do not “derive benefit” from [James],” he said. Rather, “he “does me good”. I find him visibly and testably right – right in intuition, range of considerations, sequence of reasons, and fully rounded power of expression. He is for me the most inclusive mind I can listen to, the most concrete and the least hampered by trifles.” It’s tough to improve on Barzun’s sentiment and impossible for me to outclass his endorsement, so I won’t try. In James and Cajal we have two master expositors who aren’t just good for us, but who continue to do us good. I’ve found them to be reliable antidotes to my own cynicism and small-minded-ness, reliable rekindlers of the flame. I’m looking forward to sharing them with you, and taking this big plunge together.

Leave a comment