Summary of ‘The Principles’ — Chapter 1, part 2.

James barters a truce between the associationists and spiritualists and essentially says: hey, I think we can all agree that the brain has something to do with mental life, regardless of what our philosophical commitments are. Whatever other sort of ‘ists’ we are, we are all “cerebralists”, to use James’ more colorful language. Like it or not, the brain forces its way to the center of many conversations about mental life, and “certain peculiarities” of our behaviors rest on brute facts about our brains. He’s a little bit slippery about what exactly the relationship is between bodily facts and mental facts (and how could you not be!), but ends up settling on the agnostic claim that “no mental modification ever occurs which is not accompanied or followed by a bodily change.” That pretty much keeps everyone happy (enough), and is all he really needs to give himself a biological toehold on mental life. He basically wants us to admit, I think, that it would be foolish to pretend that careful observation of an organism’s actions has nothing to tell us about its mind. And widening the circle: careful observation of action, in general, has something to tell us about minds, in general.

So what kinds of actions are we talking about? Are even simple reflexes also Psychological/mental acts? What about complex behavioral sequences that seem to be executed instinctually and procedurally, and without the lights on? Don’t overthink it, James says. “At a certain stage in the development of every science, a degree of vagueness is what best consists with fertility.” Remember that gem the next time you feel tempted to answer someone with the more pedestrian “the f** if I know!”

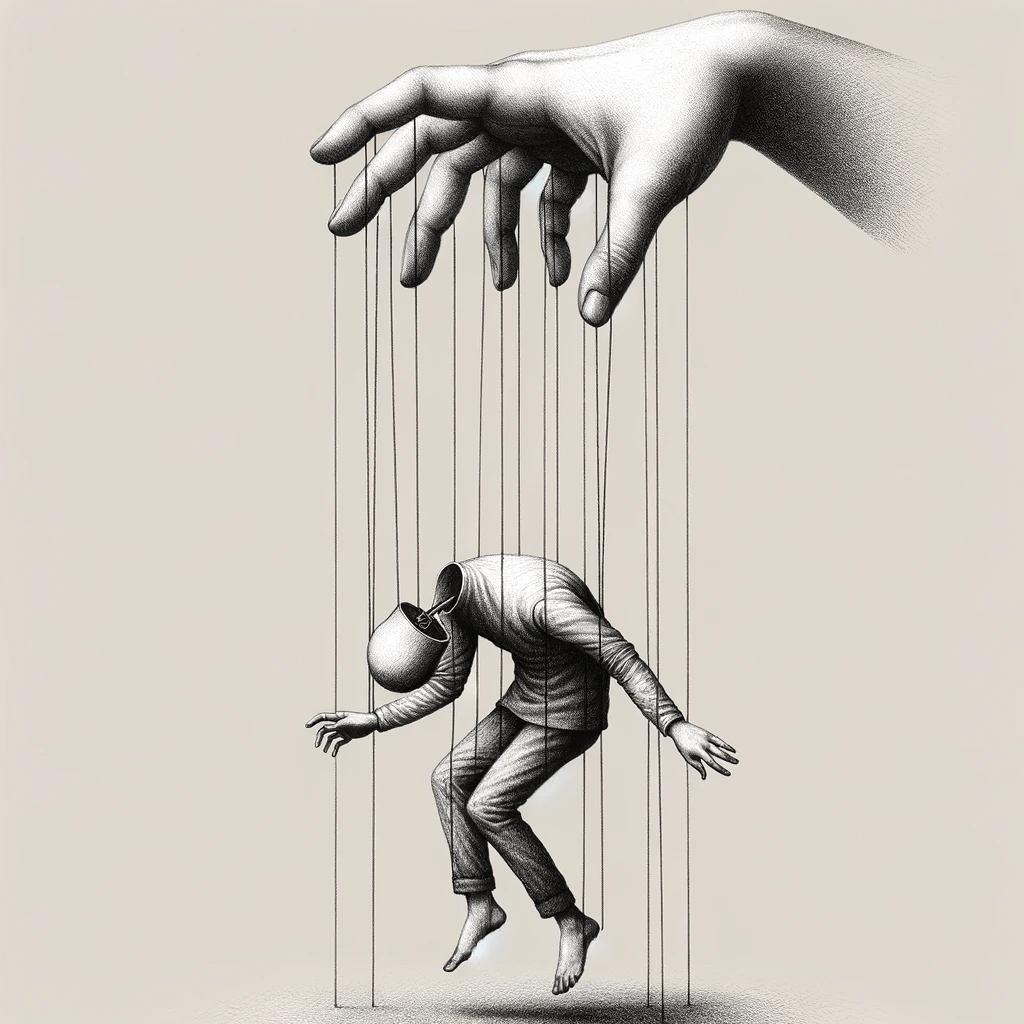

What James really wants to do is think about 1) animal movements and behaviors, and also think about 2) inanimate objects’ movements and behaviors, and then think carefully about the differences between them. Whatever is left over when we subtract the second from the first is what it means to have a mind. For James, ” the pursuance of future ends and the choice of means for their attainment are thus the mark and criterion of the presence of mentality“. Basically, when your movements are interrupted and your goals are thwarted, you can try things another way. A ball rolling down a hill can’t do that. We can be pulled by the future, while the ball can only be pushed by the past.

” the pursuance of future ends and the choice of means for their attainment are thus the mark and criterion of the presence of mentality“

William James, The Principles of Psychology

The examples James uses to get this idea across are great, and his exposition is a masterclass in scientific communication. You should definitely just read the original. To give a quick synposis, he has us imagine some iron filings sprinkled on a table. When we introduce a magnet, we see that the filings are attracted to it. But it’s a pretty dumb and teleologically uninteresting attraction, in the sense that if we place a card over the filings, and repeat, they’ll behave exactly the same as before, only mindlessly pressing up against the card where the magnet is. If we consider the attraction between Romeo and Juliet though, and we put a wall between them, they won’t just stand there “idiotically pressing their faces against it’s opposite sides.” They’ll find a way! The mind is the thing that finds a way.

Leave a comment