In the previous section on the nervous system, James gave us permission to think teleologically about the brain (i.e. the brain executes actions that are ‘appropriate’ for a useful outcome). He also urged us to think about the brain in a hierarchical way, supporting behaviors ranging from completely automatic (reflexes) to fully volitional (complex acts we decide in advance to do, or at least seem to). Do we find this presumed hierarchy of behavior types instantiated in the anatomy and organization of the brain?

“Whereas the ‘lower’ brain areas execute a strict and invariant mapping from stimuli to appropriate responses, ‘higher’ brain areas, in James’ view, respond to stimuli in ways that are fuzzy, noisy, variable, and therefore not completely predictable. We’re not human because we process sensory inputs by some especially complicated set of rules, but rather because we break the rules that try to capture us.”

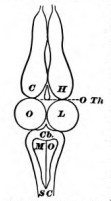

To address this, James walks us through a virtual dissection of a frog, with the grisly premise that we will start lopping off and tossing away bits of its brain starting at the front, making our way toward the back, and keeping track of what functions are lost with each new cut. It’s very well known (and was in James’ time too) that the more phylogenetically recent parts of the nervous system (like the frontal cortex) are closer to the animal’s snout, and the more ancient parts (like the medulla and spinal cord) are toward the tail. So as we work our way backwards with our cuts, we’re kind of rolling back the mind’s operating system to an earlier version. Or so one could argue. James goes at this endeavor very much in the spirit of “neuroscience is experimental philosophy.” He refers to the picture of the nervous system that results from this as “the Meynert scheme”, after Theodor Meynert, the scientist who is generally credited with it. Its held up pretty well in broad strokes, and is the basic scaffolding for today’s typical Intro Neuro style lecture on brain anatomy. That said, James acknowledges that it is definitely highly schematic, and he’s quick to note he’ll be offering corrections to it later.

(To make the exercise a bit more aspirational, James actually has us think about the gains of function we get as we add back more brain, rather than what we lose as we discard more).

We first consider a purely ‘spinal’ frog that’s had its cerebral hemispheres entirely excavated, and is basically just a spinal cord in a body. What can this animal do? Not much. It does nothing spontaneously, and doesn’t right itself when turned on its back like a normal frog would. And yet…. there are still some quite striking behaviors to which James ascribes “teleological appropriateness.” For example, if you irritate a part of its upper leg, it will try to kick at the site of irritation with the lower leg on the same side. If you remove the means for kicking (i.e., you cut off the lower leg, leaving only a stump in this poor creature), it will now wipe away the irritant with the opposite leg. James also speaks of a robotic and “machine-like regularity” of these actions. If you had hopes of compartmentalizing this result as applying only to amphibians and not us, James has some news for you. Some morbidly curious person that James refers to as ‘Robin’ evidently tickled the breast of a decapitated prisoner and found the same behavior. Yikes.

“The spinal cord in other animals has analogous powers. Even in man it makes movements of defence. Paraplegics draw up their legs when tickled; and Robin, on tickling the breast of a criminal an hour after decapitation, saw the arm and hand move towards the spot. Of the lower functions of the mammalian cord, studied so ably by Goltz and others, this is not the place to speak.”

James, The Principles of Psychology (1890)

If the spinal cord is the nervous system’s cone, then the first scoop of cerebral ice cream would include structures of the hindbrain such as the medulla. Adding these back to our hapless frog, James finds that he recovers basic rhythmic behaviors such as swallowing and breathing — things that we now appreciate are handled by so-called central pattern generators (CPGs) in the brainstem. Our “brainstem frog” can right himself if tipped — a new trick that the ‘spinal frog’ lacked — but won’t climb up on a board.

When we add back the next scoop, which includes the thalamus and optic lobes (parts of the low forebrain and midbrain, above), the frog seems to now move around quite normally both on land and in the water. Even though this “diencephalic frog” (as we might call it today) has a fairly normal repertoire of behaviors, James makes the point that it doesn’t initiate any activity. It is an “extremely complex machine whose actions… tend to self preservation; but still a machine, in this sense — that it seems to contain no incalculable element.” (emphasis mine). Continuing, James notes that by “applying the right sensory stimulus to him we are almost as certain of getting a fixed response as an organist is of hearing a certain tone when he pulls out a certain stop.” These are lovely turns of the phrase, and it’s an important moment in The Principles because it smuggles in some metaphysics. Whereas the ‘lower’ brain areas execute a strict and invariant mapping from stimuli to appropriate responses, ‘higher’ brain areas, in James’ view, respond to stimuli in ways that are fuzzy, noisy, variable, and therefore not completely predictable. We’re not human because we process sensory inputs by some especially complicated set of rules, but rather because we break the rules that try to capture us. We do weird things like relax into our pain, and find niceness sickening.

James leaves us with a couple of takeaways after the dissection exercise, which have profound implications for his project. After playing philosopher for a few pages, he pivots into engineering mode, and thinks about implications of the findings for a theory of neural control:

First: Each neural center seems to have access to the musculature, and utilizes it competently. It’s not like the spinal cord, if left to its own devices, just discharges at random and causes the legs to contort in spastic and unnatural movements. Instead, it executes familiar motions like ‘wiping’ and ‘kicking’. As we ascend toward the cortex, we’re not so much recruiting new muscles, as we are using them in more novel combinations, and with a different ‘telos’, you might say (reflex –> ‘semi-reflex’ –> volitional act). More modern work has actually found a lot of the low-level pattern generators that James is anticipating here.

Second: As a corollary to the above: The same muscles are represented redundantly at different levels of the motor hierarchy. The lowest center is a puppeteer of muscle, and the higher centers are puppeteers of puppeteers — like “a general ordering a colonel to make a certain movement, but not telling him how it shall be done.”

Leave a comment