James is definitely trending into Neurophilosophy here, and tries to map some moral and ethical notions onto considerations of brain circuitry. Quite conveniently, the brain he describes seems designed to instantiate 19th century New England Protestant virtues. I think he’s getting a bit intellectually greedy and ahead of himself here, but the tone isn’t pushy, and he’s certainly not arguing dogmatically for some kind of strict moral system that comes from reading the cerebral tea leaves. At the end of the day, if humans have any “virtuous” behaviors that other animals lack, or which are present to a lesser degree, these would presumably have to show up in brain circuitry somehow. James’ register here is very New England transcendentalist, preacherly in an Emersonian ‘student of nature’ sort of way. This stuff ran in James’ blood. Emerson was enough of a fixture at James’ childhood home that the guest room was referred to as “Mr. Emerson’s room.”

The big concept we get in this section, and which finds its way into all of James’s subsequent work is that of “obeying the absent.” This is what sets humans apart morally, ethically, and ultimately physiologically from what the 19th century referred to as “the brutes.” Whereas the lower brain centers (in James’ view) act only in response to what is present (“present sensational stimuli”), the ‘hemispheres’ are the seat of all the additional imagination, narrative, and delusion that we append to sensory stimuli. (You know, the lovely rumination and self-inflicted torture that continues for hours after the phone call or the conversation is over). The stuff that has the greatest psychic pull on us, and which is most worth living for is the stuff that’s quite.literally.not.really.there. James gave us the first glimmer of this idea in his 1878 essay entitled “Remarks on Spencer’s Definition of Mind as Correspondence.” Not exactly a clickbaity title, but it lays down much of the important philosophical scaffolding for The Principles and for The Varieties of Religious Experience (which has a chapter entitled “The Reality of the Unseen” ). From “Remarks on Spencer”:

The ascertainment of outward fact constitutes only one species of mental activity. The genus contains, in addition to purely cognitive judgments, or judgments of the actual […] an immense number of emotional judgments: judgments of the ideal, judgments that things should exist thus and not so. How much of our mental life is occupied with this matter of a better or a worse? How much of it involves preferences or repugnances on our part? We cannot laugh at a joke, we cannot go to one theater rather than another, take more trouble for the sake of our own child than our neighbor’s; we cannot long for vacation, show our best manners to a foreigner, or pay our pew rent, without involving in the premises of our action some element which has nothing whatever to do with simply cognizing the actual, but which, out of alternative possible actuals, selects one and cognizes that as the ideal.

William James, “Remarks on Spencer’s Definition of Mind as Correspondence” (1878)

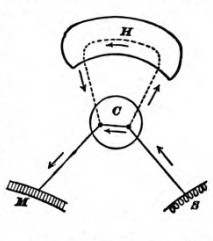

In The Principles, James gives us a more pedestrian illustration of the reality of the unseen by having us imagine going on a stroll and seeing a rattlesnake. Even if we’re not bitten, we’ll still feel all manner of terror, have visions of pain and suffering that our minds have dredged up from experience and imagination. James sees a critical role for memory here, and even gives us a quaint little circuit diagram to explain things.

In the figure, sensory inputs (‘S’) are ordinarily routed through the nervous system (‘C’ ), which cause the muscles (‘M’) to discharge — the so-called “direct line”. The hemispheres (‘H’) constitute what James calls a “loop line” that operates outside the simple sensorimotor pathway. That’s where sensation detonates memory and imagination, which then influence behavior after a bit of a synaptic detour.

And here’s where we get preachy. Why, a “tired wayfarer” might find himself needing to rest on a hot day, James tells us, the “sensations of delicious rest and coolness pouring themselves through the direct line.” Should our wayfarer succumb to the direct line’s sensory mandate, and enjoy a midsummer’s rest in the shade? Hell no! He needs to keep going, dammit, like a good god-fearing subject! And that’s where the long loop comes in. “[T]he loop line being open, part of the current is drafted along it, and awkakens rheumatic or catarrhal reminisces, which prevail over the instigations of sense, and make the man arise and pursue his way to where he may enjoy his rest more safely.” The neuroscience of delayed gratification. Or, to cast it into a nineteenth century idiom: the neuroscience of ‘prudence.’

Without the long line circuit, James elaborates, no animal would be able to “deliberate, pause, postpone[…] or compare.” “Prudence, in a word, is for such a creature an impossible virtue.” Riffing on the prudence theme, he moves on to consider the appetites, proposing that the long line is what prevents you from just snapping reflexively at every morsel that’s placed in front of you. Lacking this, you could no more disobey the tempting lure of the senses than water can refuse to boil when placed under a fire. And in case the moral dimension needed spelling out, James lets us know that for such a creature “life will again and again pay the forfeit of his gluttony.” As with appetites for food, so with sexual appetite. In frogs and toads, where sexual behavior is handled by the direct line, as it were, one observes a “machine-like obedience to the present incitement of sense, and an almost total exclusion of the power of choice.” He gives us what may well be the most unforgettable description of mindless sexual fecundity ever put to paper:

“Copulation occurs per fas aut nefas, occasionally between males, often with dead females, in puddles exposed on the highway, and the male may be cut in two without letting go his hold. Every spring an immense sacrifice of batrachian life takes place from these causes alone.”

James, The Principles (1890)

The long line of our brain helps nullify the fundamental gluttony and wastefulness that animate us. It holds the dangerous, unbridled powers of consumption and propagation in check. Immediately after this gem, we make a very Jamesian pivot from headless frogs copulating with corpses in roadside puddles to people in high society: “No one need be told how dependent all human social elevation is upon the prevalence of chastity.” (Evidently, we did need to be told….)

James leaves us with a kind of taxonomy of the virtuous, basically spelling out the idea of prudence in the idiom of neuroscience. (Apologies in advance for what will strike many modern readers as a judgey, dated tone):

“The tramp who lives from hour to hour; the bohemian whose engagements are from day to day; the bachelor who builds but for a single life; the father who acts for another generation; the patriot who thinks of a whole community and many generations; and finally, the philosopher and saint whose cares are for humanity and for eternity,—these range themselves in an unbroken hierarchy, wherein each successive grade results from an increased manifestation of the special form of action by which the cerebral centres are distinguished from all below them.

James, The Principles (1890)

Leave a comment