The view of the brain that James is teeing up for us so far is basically a “reflexological” one. That is, we’re essentially bundles of simple reflexes that are blindly pinging across the brain’s lower centers, with the cortex (the ‘hemispheres’) sitting on top, chaining these reflexes together and making them contingent on one another in various clever and adaptive ways. The chaining-together is a product of experience, and essentially serves as a memory trace, and James is quick to tell us that “[a]ll ideas.. [are].. in the last resort reminisces”. I honestly don’t have a great handle on what James means, exactly, by an ‘idea’, but I think he’s basically defining it by exclusion, and almost a bit tautologically. If reflexes are something like the streaming content of the nervous system, in which currently present stimuli immediately beget behavioral responses, then ideas are everything going on in the brain that’s not that.

The scheme James proposes is, well, really schematic, and not how many researchers think of the nervous system today. At the same time, it would be impossible to overstate its influence.

So, how does all that chaining together happen in the hemispheres, under James’ model? As he puts it: “How can processes become organized in the hemispheres which correspond to reminisces in the mind?” The specifics he offers are so vague and quaint as to be almost a little bit embarrassing to summarize (and I think he knows this), but he still gives us a really useful logical scaffolding for constructing any science that would try to equate brain activity and mental activity. He starts by giving us a set of four assumptions that have a “big ideas in Neuro” feel to them. I’m struck by how this prefigures much more modern ideas about the cell assembly that we’ll see later in the work of Donald Hebb. James’ assumptions are (paraphrasing):

- An ‘idea’ (i.e. memory) in the brain looks really similar to the original sensory object that it’s mimicking/representing. If you think of a rose, someone looking at your brain would see a pattern of activity that’s quite similar to when you’re actually seeing a rose. A huge amount of neuro research is premised on this, even today. In fact, whole fields are unimaginable without it.

- “Cells that fire together wire together.” That famous phrase by Donald Hebb means that a set of neurons activated in succession will tend to link up together, so they’re more likely to be recruited together in the future. James was way ahead of his time, but unfortunately didn’t know about neurons, so he instead had to vaguely describe “processes.” His original:

- “If processes 1, 2, 3, 4 have once been aroused together or in immediate succession, any subsequent arousal of any one of them (whether from without or within) will tend to arouse the others in the original order. [This is the so-called law of association.]”

- Sensory inputs flow ‘upward’ to the cortex — the land of ideas — in addition to mediating lower-level reflexes.

- ‘Ideas’ serve the function of promoting or inhibiting behavior, even if that influence is pretty distant.

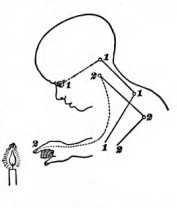

With those assumptions in hand, James gives us a kind of just-so reflexological story about a child reaching out toward a flame, and how it is that he learns he should definitely not do that again in the future. The first time the child sees the flame, the “reach for the pretty thing” reflex (pathway 1, in the diagram on the left above) is activated. Because that reflex is blindly obeyed, the “ouchie” reflex (pathway 2) is recruited when the finger enters the flame, and the hand pulls back. Before encountering the flame, pathway 1 isn’t talking to pathway 2, and if there was no learning, this process would presumably repeat indefinitely, with the finger being char-broiled after a few iterations.

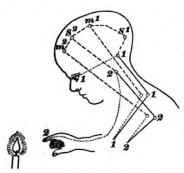

Enter the hemispheres and the ‘loop line’! James gives us a pretty dense figure (above right) to parse about all the connections that are formed, but the basic idea is that a new sensorimotor pathway is formed in the hemispheres that directly links up the sight of the flame (sensory) to retraction of the hand (motor), and which acts to oppose the “reach for it” reflex. The chain of succession is always sensory->motor, such that the sensory trace of one process activates the motor trace of another. Interestingly, James was again ahead of his time in proposing the idea of a motor trace (or what we’d now call an efference copy) — a neural echo not of a stimulus that was observed, but of a movement that was made.

James is pretty tickled by this general idea (“it is so concordant with the … facts as to almost impose itself on our belief… “), but acknowledges that details matter and that they definitely aren’t all on hand. Like any schematic, it introduces dissociations of function that are probably nowhere near as strict or clean as implied. He says as much, noting that down the road he suspects he’ll have to grant that the ‘hemispheres’ are a bit more machine like than he’s let on, and that the ‘lower centers’ are less machine like. He was right to hedge like that. While the strict anatomical dichotomy of the lower centers vs. the higher centers is an overreach, there is still a useful functional dichotomy between hard-coded vs flexible circuits that guides a lot of modern research.

Leave a comment