James wraps up his chapter on the brain by offering his final “correction” of the Meynert scheme, and these corrections are important for his later considerations on the role of the will, instincts, and emotions in behavior. I don’t know what the intellectual climate was at the time, but it seems like Meynert’s ideas (which are themselves a kind of anatomization of John Locke’s ideas about the tabula rasa) were something like the field’s consensus. Up till now, James has given a respectful tour of their virtues and the evidence in favor of them, but now wants to let us know which parts are a little too tidy, and a little too good to be true.

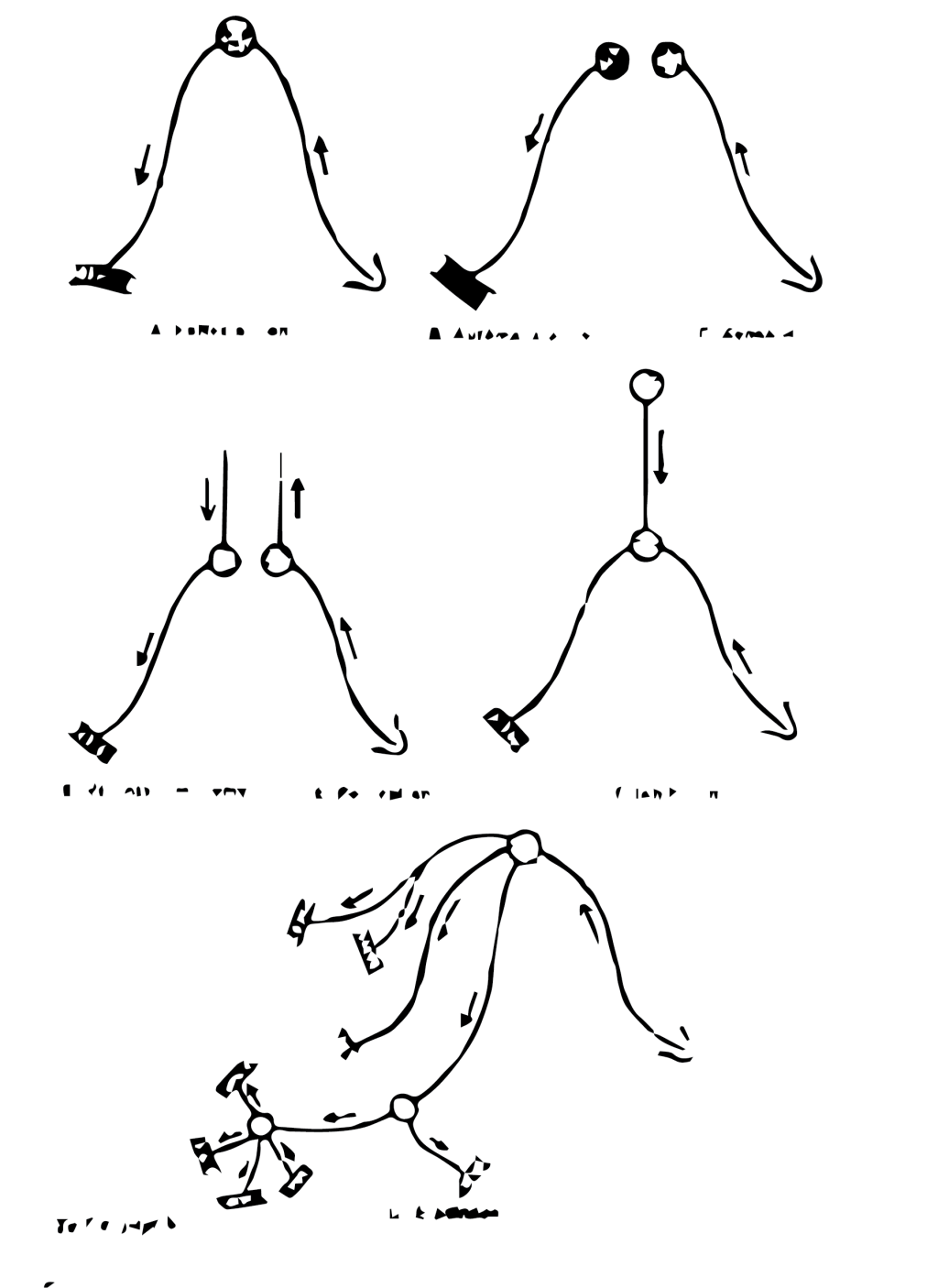

The philosophical core of Meynert, according to James at least, is expressed in the baby-touching-the-flame diagram. You’ll recall that the idea there was that reaching for the flame, on sight, and retracting from the the flame, on pain, were two untutored reactions that were prompted by stimuli, and handled by low-level brain structures. Meynert’s “hemispheres” sat on top of these reflexes, and chained them together in ways that were useful and adaptive. Two key notions of this scheme are that: 1) The “low centers” (which dispatch the reflexes) act natively and robotically, and are purely driven by stimuli, and 2) The “hemispheres” have no causal powers on their own, and aren’t in the business of reacting to candle lights and burns until they’ve had occasion to learn something relating the two.

Both of these ideas are wrong, according to James, and the more you ascend the great chain of being, from fish to birds, to dogs, to monkeys, to people, the more wrong they are. He hits us with a few observations that are hard to accommodate under the strict Meynert scheme, like birds and frogs actively pursuing food (behaving spontaneously) even when their hemispheres have been removed.

James argues for the idea that the hemispheres come pre-configured to a degree that Meynert doesn’t appreciate, and that they must have “native tendencies to reaction of a determinate sort.” Further, he thinks these native tendencies are things like the emotions, and instincts, which he conceives of as kinds of reflexes. (Sometimes it seems like everything was a reflex, either simple or complex, to nineteenth century neurologists). In any case, what makes these complex functions still reflexes is that they don’t have to be trained, don’t require deliberation, and are “irresistible.” (great word!)

James leaves us with a modification to Meynert that he acknowledges is “vague and elastic”, and he also ends on a note of characteristic humility, saying that trying to cover complex and disparate facts of any kind with an all-encompassing general formula is going to quickly expose gaps in our understanding. He gives us the speculative idea that each of the brain centers harbors or at one point in its phylogenetic past harbored a kind of proto-consciousness, by which he specifically means the mental powers (and their attendant biological mechanisms) for 1) preference, 2) recognition of the ends of desire, and 3) a notion of the means for attaining desires. He’s proposing a kind of natural history of experience, and these map on to ideas he develops much more extensively in The Principles about attention (preference), memory (recognizing the ends of desire), and will (means for attaining desire).

Under the Jamesian view of consciousness as admitting many intermediates and evolving from simpler forms, he paints us a picture of how consciousness may have elaborated in the brain. He sees it as a process of bootstrapping and distillation over the course of evolution, in which lower structures pass into a more “unhesitating automatism”, and higher structures rise toward “larger intellectuality.” It’s kind of a neat (if impossible to answer) question what the right metaphor for succession is here. Is it something like ‘conquest’, where new areas are subduing and suppressing the old? Or reform? Upheaval?

Leave a comment