(So, I lied when I said in my original blog post that we’d trade off between James and Cajal a chapter at a time. I’m going to move on to chapter 3 of The Principles because in many ways it’s a continuation of the previous one. I suspect that for the presently –well– ‘lean’ readership this will be little cause for outrage ;-)).

James has already given us a good dose of neuroanatomy in the previous chapter, touching upon the brain’s plasticity, the localization of function, and exploring whether all mental events and behaviors are just reflexes strung together. Apart from the simple just-so story of the child learning to withdraw his hand from a flame, though, there wasn’t much of an attempt to catch the brain in the act of having a thought.

In this chapter, James tries to play neuroscientist and develop some intuitions about the exact mind/brain relationship. Needless to say, the state of Neuroscience in 1890 was pretty rudimentary, and he knows that fundamentally, he’ll need to “relegate the subject of the intimate workings of the brain to the physiology of the future.” Cell theory was really just starting to make inroads into the brain, and obviously there was nothing like the science we have today that lets us measure electrical activity from single cells, identify and track populations of neurons, and interrogate neural circuits with spatially targeted stimulation. So everything James discusses about brain activity is only vaguely gestured at as “currents” propagating along “fibers.” Nevertheless, he starts off with a still-relevant public service announcement and cautions us against adopting a kind of tinker-toy version of neuroscience, in which single cells are taken to represent single ideas, and their anatomical interconnections indicate webs of mental association. That’s not to say cells have nothing to do with ideas, and connections have nothing to do with association. “In some way… our diagram [of mental activity] must be realized in the brain,” James writes. It’s just that it’s “surely in no such visible and palpable way as we at first suppose.”

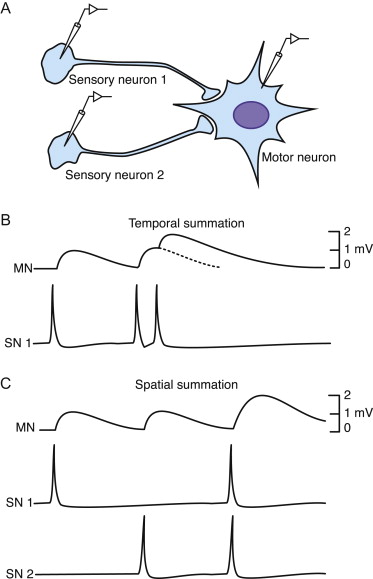

Lacking a clear anatomical understanding of neurons (single brain cells), as well as a compelling theory of their electrical behavior, there’s not much James can say about how brain activity might be organized in space. But he’s got a bit more of a leg to stand on in discussing how brain activity is organized in time, and he makes some very ingenious deductions from simple but consequential experiments about reaction time (more on this in the next post), as well as experiments on the summation of activity in the nervous system.

Temporal and spatial summation are well known phenomenon in the brain, and basically amount to the idea that tiny nudges and tickles that are individually too wimpy to elicit behavioral responses can be added up to be an effective stimulus. Eventually, James tells us, with enough small stimuli packed closely together in time or space, there will be a straw that breaks the camel’s back, and which makes something consequential happen. It’s a simple enough idea, but has a lot of explanatory power, and is still used to explain things like decision times and reaction times with a surprising degree of quantitative precision. In typical Jamesean fashion, we get lots of homespun examples about the phenomenon. One of the more memorable ones is of “street hawkers,” who line up along the streets, with the last one in the line often being the one passers by will buy from, “through the effect of reiterated solicitation.” James intends to leverage the idea of summation really hard in future chapters, and assures us that his theories of “Instinct, the Stream of Thought, Attention, Discrimination, Association, Memory, Aesthetics, and Will will contain numerous exemplifications of the reach of the principle [of summation] in the purely psychological field.” Pretty damn bold, but when you’re a literary and scientific genius you can get away with it.

One neat point he argues is that we don’t really have grounds for saying that only supratheshold activity (that which has cleared the threshold for causing an action, or a muscle contraction, or a ‘spike’ of neural activity) is what contributes to consciousness. Instead, he thinks that “submaximal” and “outwardly ineffective” activity may “have a share in determining the total consciousness […].” There can be a tendency even today to be something of a suprathreshold chauvinist, and to tacitly think of thought as something like a series of concrete and indexable ‘results’ of integration. James doesn’t think of thought this way at all. Rather, he sees it as a contiguous flow, where all the intermediates, pirouettes and transitions matter, so it’s natural that he wants ongoing subthreshold activity to be taken seriously in its own right. In fact, he even states that “without [subthreshold activity’s] contribution the fringe of relations which is at every moment a vital ingredient of the mind’s object, would not come to consciousness at all.” Later, in the famous chapter on the stream of thought, we get this idea many different ways until we’re hit with the conclusion:

“Consciousness, then, does not appear to itself chopped up in bits. Such words as ‘chain’ or ‘train’ do not describe it fitly as it presents itself in the first instance. It is nothing jointed; it flows. A ‘river’ or a ‘stream’ are the metaphors by which it is most naturally described. In talking of it hereafter, let us call it the stream of thought, of consciousness, or of subjective life.“

As much as I love this at a metaphorical/literary level, I don’t know that the apparent contiguity of thought requires that subthreshold activity makes a contribution to consciousness. But James still has about a thousand more pages to convince me.

Leave a comment