This is a little bit of an oddball section where James talks about cerebral blood supply, and where he weighs in on the issue of the unique role of phosphorous in thought (evidently this was contended strongly enough in his time that it gets a special mention here).

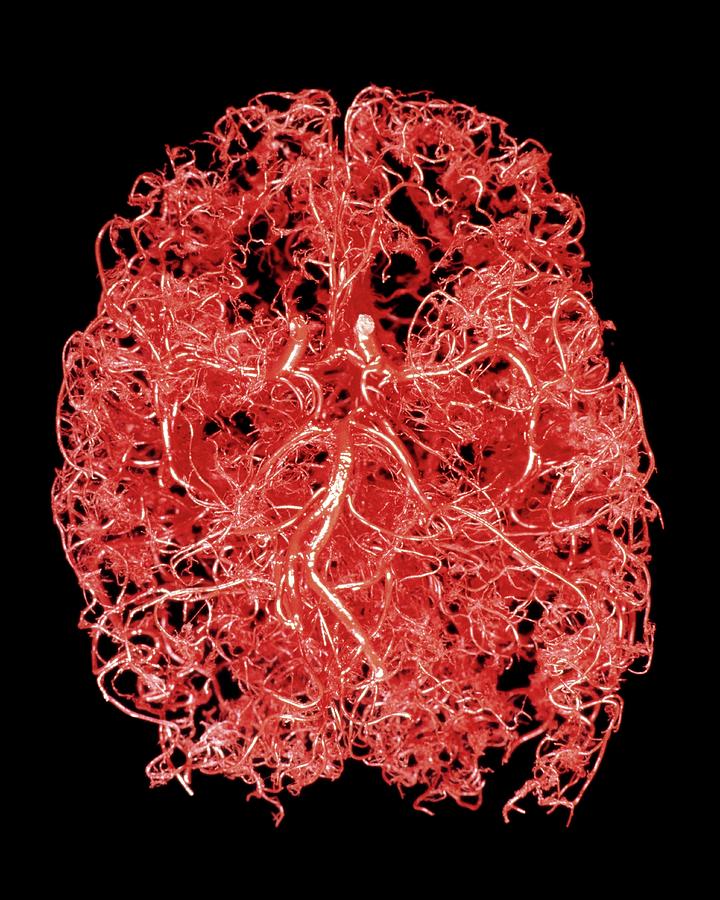

We have such an inflated and mystical view of the brain that we forget that in addition to being the seat of reason, emotion, and all that, it’s still an organ. That being the case, it needs to have access to a fresh supply of blood, or bad things are going to happen. By the numbers, it’s a positively bloodthirsty organ, with cerebral bloodflow being typically about 15-20% of cardiac output (the kidneys actually still beat it out, utilizing about 20-25% of cardiac output). If you’ve never seen an image of what blood supply to the brain looks like, you should check it out. It’s ridiculously impressive. In resin casts, or in tissue where blood vessels have been labeled, you just see a dense and tangled nest of capillaries that almost completely fills space. You can’t help but have the thought: where the hell do all the brain cells fit?! It’s easy to see why the Greeks thought the brain was basically just an organ for filtering and cooling the blood. “The brain itself is an excessively vascular organ” James tells us, quite correctly. “[A] sponge full of blood, in fact [..]”

Modern fMRI studies are all premised on the tight dynamic relationship between cerebral bloodflow and neural/mental activity. While the fancy “Magnetic resonance imaging” part is a recent-ish invention, we’ve known about the blood-brain link for quite a while, and James gives us a summary of what was known circa 1900. In addition to describing the slightly unsettling observation that electrically stimulating the brain changes blood pressure throughout the body, he also summarizes the ingenious experiments of Mosso, who showed that arterial pressure in the brain changes when people are engaged in mental activity. Mosso also designed a balancing table that he had experimental subjects lay on, and which could tilt like a seesaw toward the head or feet as blood was redirected toward the upper or lower extremities. When people did mental arithmetic, or were made to have emotional reactions, “down went the balance at the head-end, in consequence of the redistribution of blood […]” as James tells it. Interestingly, James makes the observation that “blood very likely may rush to each region of the cortex according as it is most active, but of this we know nothing.” He was indeed right in his hunch, and in fact this is what makes functional brain imaging possible.

After hearing about bloodflow, we learn a bit about how the brain gives off heat, and more so when engaged in thought. Evidently even scalp measurements of temperature change when doing mental arithmetic and reciting poetry. We even get the delightful observation that temperatures rise more when reading poetry silently than when reading it aloud. James’s explanation? To speak is aloud while thinking is the simple and natural process; suppressing this requires inhibition, which consumes energy. (I have no clue if these observations, or the explanation, really hold up — just reporting the argument here).

In the overall metaphysics of The Principles, I think the bloodflow/temperature observations are here to underscore the idea that however mysterious thought is, it’s still an organic phenomenon, a process requiring nutrients, consuming oxygen, and producing wastes that need to be cleared out.

After bloodflow and cerebral calorimetry, we hear a bit about “Phosphorous and Thought.” One gets the sense that James is discussing this idea reluctantly, out of an obligation to dismantle a mostly silly theory that’s regrettably believed by a fair number of serious people. (We all have a few of these in our lives, don’t we? 😉 )”Ohne Phosphor, kein Gedanke” (“no phosphorous, no thought”) was a rallying cry of the era, and it was supposedly backed by experiments showing changed levels of phosphorous in the urine after episodes of mental activity. This all sounds rather silly to us now, but the sentiment is still alive and well today in countless popular science pieces that make essentialist arguments about the role of Dopamine, or Serotonin, or Cortisol, or whatever the neurochemical du jour is.

Leave a comment