So, we’re setting aside James for a bit, and moving on to the first chapter of Cajal’s Textura. Whereas James is an explorer of inner life in the sense of that which is available to introspection, Cajal explores the inner, skull-bound world which is visible with a microscope. He wants to understand how neurons (brain cells) in all their complexity, beauty, and exuberance account for properties of sensation, thought, and movement.

He begins his famous tome in a characteristically romantic key:

“The nervous system represents the ultimate boundary in the evolution of living matter, and the most complicated machinery of noblest activities that Nature has to offer.”

We can immediately see that, like James, Cajal is an evolutionary thinker who has a deep respect for the comparative approach — one that freely roves over different scales and phyla. Matter has been permuting and morphing and self-organizing for eons, and this process has a fringe. And that fringe, for Cajal, is us and our brains. If there’s nobility in the universe, we’re it. Let there be no doubt about how seriously Cajal took his life’s work!

In the first chapter, Cajal tackles the formidable question of what nervous systems are up to, and what teleological ends they serve. He regards the brain as “an apparatus of improvement,” that accentuates “the unity of the living being”, and which is attaining, over time, ever more “precision, efficiency, and congruency.” This isn’t some kind of unfolding of cosmic perfection though. Rather, it’s an engineering-like effort to marshall better resources to obtain food and defend against “attacks of the external world.” In pursuing these ends, the nervous system has pushed, over evolutionary time, in the direction of greater specialization and more division of labor/function, while trying to work within constraints of speed, precision, and wiring economy.

The first big principle Cajal articulates is the division of nervous system function into sensory and motor aspects. Life is fundamentally ‘oriented’ in the sense that all living forms both act and are acted upon, must both ‘do’ as well as ‘detect’. The metaphysics of cause and effect is deeply knit into us. As our bodily plans become more complex and make us responsible for a larger “field of action” (as Cajal refers to it) this tends to be matched by cleaner and sharper divisions between sensory function and motor function.

He illustrates this by way of example. In a simple single-celled organism with limited means for movement, the cell membrane serves the receptive sensory role, and is capable of being agitated by chemicals and mechanical pressure. These agitations of the membrane are diffusely and relatively directly coupled to motile elements of the cell — the distributed network of filaments that can be mobilized to change the cell’s shape, navigate toward food, etc. So, sensory and motor aspects in this ‘simple’ organism are functionally distinct, but also a bit messily intermingled.

But let’s extend our cell’s field of action, Cajal has us imagine, by now giving it a tail-like flagellum. We don’t just want that flagellum whipping around willy-nilly. That would be wasteful. Instead, we want to make its expensive, energy-consuming whipping conditional on very particular environmental conditions (“food is nearby — keep going”, or “smells like bad news in this direction — spin us around”). That will create a teleological nudge, Cajal surmises, toward “the localization or concentration of sensory capacities in certain sites that were distributed before throughout the cell body.” Additionally, Cajal notes, this will probably also start to establish “preferred routes within the protoplasm for the propagation of the sensory excitation, and easier paths for the transmission of motor reactions.”

There are only so many ways to functionally specialize and divide sensory and motor labor, though, within the aqueous and oozy interior a single cell. Being multicellular buys you enormously more possibilities, and this is the niche the nervous system has explored to great effect, creating a veritable zoo of cellular subtypes.

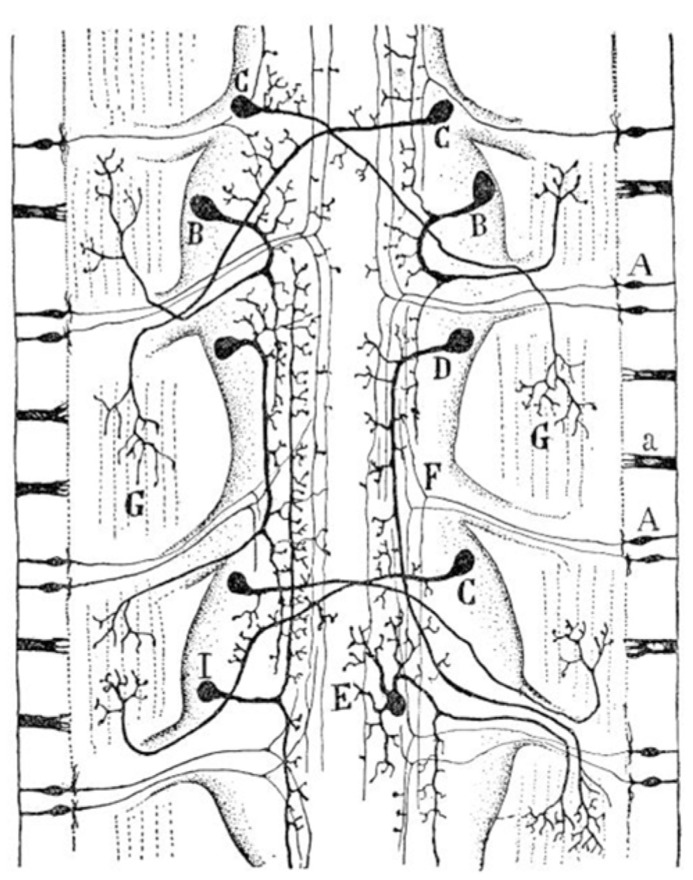

To get us to appreciate this, Cajal takes us on a tour of a few different multicellular (but still ‘simple’) critters. First up: the sponge — a kind of counter-example. Sponges have no nervous system, but they do have a rudimentary division of labor in the sense that each of its cells cell relies on other cells doing their job. Next up: the worm. Worms are today a very intensively studied model nervous system, but in the Textura, Cajal though of them as a kind of transitional form to make a point about simple forms of sensorimotor communication. Unlike sponges, these animals have sensory and motor neurons that communicate, but the communication is (in Cajal’s view, at least) local. If you irritate a specific body segment, you’ll get a contraction of that same segment. There are comparatively few opportunities for dynamic routing and amplification of stimuli of the type you’d need to say, swat a fly landing on your left shoulder with your right hand. For that, you need long range projections of sensory neurons that distribute widely across the body, to distant muscle groups. More on this in the next post!

Leave a comment