Like James, Cajal is a master expositor of scientific ideas. He grounds us in “didactic” examples of relatively simple nervous to illustrate basic principles, and then builds on these through successive approximations, gradually climbing the phylogenetic ladder. Today it’s not really fashionable (or correct) to talk about ‘lesser’ and ‘lower’ forms, but as a pedagogical device, the comparative approach has a lot of value.

Cajal informs us that coelenterates (jellyfish and the like) have “the first unequivocal manifestation of a nervous system.” Their cellular organization is therefore especially interesting, since they bear the principles of nervous system organization in their most nascent form. They’re the basic “code base” that evolution tinkered with and forked off of. They have bona fide sensory neurons, with a characteristic bipolar shape, and a blunt ‘knob’ that points toward the outside world. A quick glance at sensory neurons in the nose (olfactory sensory neurons) and retina (photoreceptors) gives the basic idea (see image below).

Coelenterates also have motor neurons, which Cajal describes as having a ‘stellate’ (star-like) shape. Apart from this, he holds back from saying too much about their nervous systems because anatomical studies of the time were inconclusive. I’m sure quite a bit has been cleared up since then, but this is definitely outside my area of expertise. Cajal leaves things with the jellyfish by wondering out loud whether their nervous system is as simple as it gets. Do we find both sensory and motor neurons always working in concert in the animal kingdom, or was there some proto-organism that had a single neuron type that projected directly from skin to muscle? Again: well outside my area of expertise, though I’m sure we know more now than we did in Cajal’s time — if you happen to know about this, drop something in the comments.

After our little detour with coelenterates, Cajal takes us back to the worm. We find both sensory and motor neurons in them, but in addition, they are sporting a third type of neuron — the interneuron — which basically completes our cast of characters in the nervous system. (Obviously there’s huge variety in the subtypes of cells). What’s so special about interneurons? You can immediately get the important idea from the other name Cajal uses to describe them: ‘association’ neurons. If sensory neurons ‘detect’, and motor neurons ‘do’, then interneurons handle the complex routing, distributing, linking, and switching that has to happen between ‘detecting’ and ‘doing’; they give neurons the flexibility to do more than just fire off simple brute reflexes.

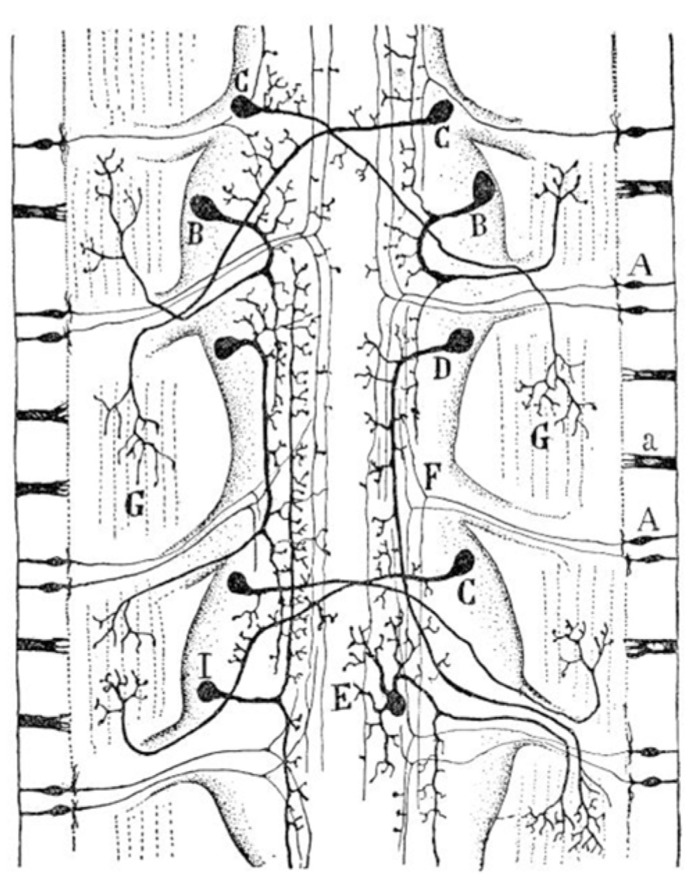

With the three critical elements in hand — sensory neuron, motor neuron, and interneuron — Cajal walks us through the nervous systems bauplan and logic using the worm (again) as an example. His figure below is a classic, and is worth careful study.

Here, we’re looking a little section of a worm’s nervous system. You can immediately note some important motifs: 1) bilateral (left-right) symmetry, and 2) modularity (a basic anatomical unit is repeated in a chain-like manner). The far left and right edges are the animal’s periphery (i.e. skin) kind of splayed out, where you can see a couple different cell types. The epithelial cells (lowercase ‘a’, on the right) don’t issue any projections, and are kind of the sensory neurons’ supporting cast. The sensory neurons proper (capital ‘A’), by contrast send a variety of long-ranging projections into the central nervous system, letting it know that something’s touching the skin. Note their characteristic ‘bipolar’ shape, with a little stumpy knob that points toward the skin, and a longer process that projects centrally. The motor neurons are those monster cells with large cell bodies that run along the midline (B, C). If you follow cell B in the upper right, you’ll see that it has a thick process that snakes around and forks off into a number of branches that terminate locally in the muscle (the broken, stippled vertical lines running along the figure).

To recap so far: neurons like ‘A’ are the sensory ‘detectors’, and neurons like ‘B’ are the motor ‘doers’ that will actually lead to muscle contraction. ‘C’ is also a motor neuron, but note that instead of branching off on the same side of the body they cross the midline and innervate muscles on the opposite side. These so-called ‘contralateral’ projections are important for coordinating complex locomotor behaviors like walking. ‘D’ is yet another flavor of motor neuron, which is notable for projecting to a segment that quite distant from where the cell body is. ‘E’ is the third and final type of motorneuron Cajal describes, which he refers to as ‘multipolar’ — it has complex branches that extend off in several directions, unlike the simpler ‘bipolar’ sensory neuron. The interneuron, labeled ‘I’, appropriately enough, seems pretty much like a motor neuron, but looking more carefully at its branching processes, we see that these don’t actually terminate in the muscles (as a motor neuron, by definition, would have to). Instead, its processes run along the animal’s long axis, and it serves as a matchmaker between sensory and motor functions.

Cajal can’t resist the temptation to breathe some life into the anatomical diagram, which he does by telling us a functional story that knits all these elements together. If there’s a light little tickle of the skin, a sensory neuron (A) will excite a motor neuron (B), causing a contraction of the muscle only in the local segment where the stimulus is. If a stronger stimulus comes along though — something indicating that “we need to get the hell outta here!” — additional motor neurons will be recruited through the network of associative fibers (interneurons). This allows for complex routing of the stimulus.

OK, that went into the weeds a little bit, but I think it was (hopefully) worth the effort. It basically has in germinal form all of Cajal’s foundational principles of nervous system organization. Almost everything else is variations on these basic themes. Certainly complex and intricate variations, but variations nonetheless…

Leave a comment