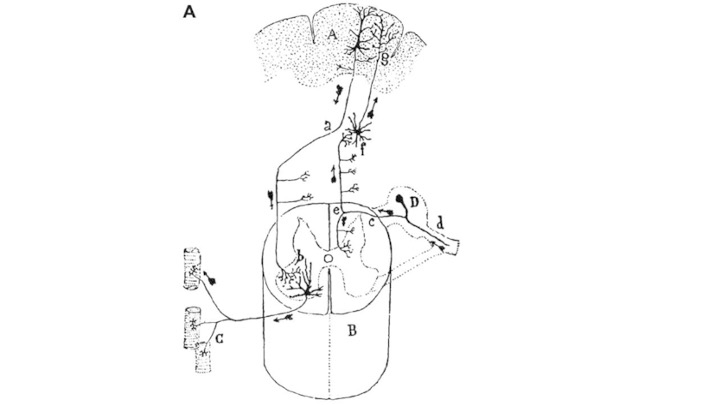

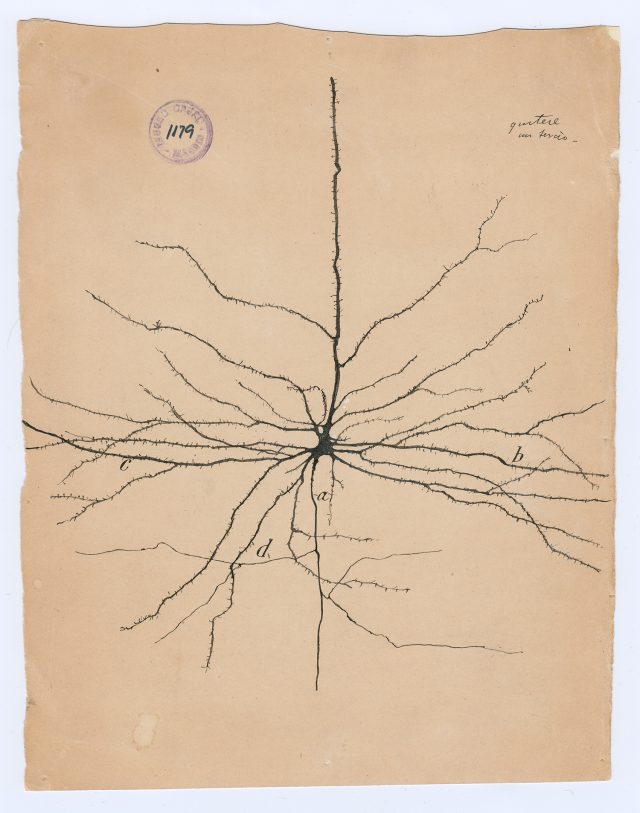

Cajal gives us a few words about a very special type of motorneuron, which he refers to as “psychomotor.” He clearly sees this as the nervous system’s secret sauce. “Its mission is to take the commands of the will to all neural foci […]. Memory, will, and intelligence emerge with it.” It’s not that the cell has any particular morphological or histological characteristics that make it remarkable. Instead, it’s remarkable by virtue of its position in the motor hierarchy. Enthroned in the cortex (see neuron ‘A’ in the figure below), it exerts top-down control over lower centers (follow projection ‘a’–>’b’), and is able to excite other motor neurons, or veto more reflexive actions. In other words, these guys are the seat of volition.

We’re also treated to a very interesting meditation on why and how these cells evolved. Cajal sees them as a kind of adaptation/specialization for handling the highly structured, detailed, and heavily formatted input that comes streaming in from the senses. The eyes and ears, Cajal says, are “true computing machines… specific collectors of undulatory energies”; they pipe in a high-def signal into the brain, and the brain has to be able to handle it in an appropriately sophisticated way. Ergo, these psychomotor cells evolved to give us conscious sensations of “extraordinary vigor and clarity.” The signals coming in from the body’s soft tissues and viscera, by contrast are comparatively “uncertain, diffuse, without precise relationships of size and shape.” And by virtue of this imprecision, their associated conscious representations will be “obscure and undetermined.” Whereas reason and intellect are freestanding spiritual faculties in the Cartesian philosophy, for Cajal they’re the product of a nervous system that’s evolving to capture the world ever more vividly, with ever sharper and more detailed imagery.

Cajal gives us a funky thought experiment for how one might test this. If we could re-route the optic nerve into the spinal cord instead of the usual cortical visual centers, he predicts that spinal neurons would accommodate the input by adopting ‘psychomotor’ morphology (which is to say, the ‘pyramidal’ morphology one finds in the cerebrum). Amazingly, experiments with this sort of flavor have been done, and support Cajal’s idea that it’s the inputs, and not pre-determined features of the recipient structures that determine morphology and functional specialization.

Of course, we can push the question back further still. Pyramidal cells have their particular elaborations because of the highly structured inputs they get from the sense organs, but how did the sense organs themselves become so organized in the first place? Cajal dutifully gives us the evolutionary standard fare about chance adaptations conferring an advantage and being retained, but in the same breath he admits that even though he knows the environment is the “probable efficient cause”, this alone isn’t a wholly satisfying explanation to him. Simply saying “adaptation + selection” fails to account for the particulars of why some ganglion and not some other evolved into a sense organ, and that bothers Cajal:

“We must confess that, even applying the principle of natural selection, it is impossible to explain satisfactorily these marvelous devices of relation with the environment which are, as we have said, the probable efficient cause of the superior dynamic hierarchy and directing role of the cephaloid ganglion, over all other ganglionic foci.”

Leave a comment