Cajal is very much an evolutionary thinker, but he also definitely sees the evolving nervous system as working toward something, in vaguely cosmic or spiritual terms. (The word ‘perfect’ appears 86 times in Vol I of the Textura… the word ‘brain’ appears 57 times). He considers, for example, the mammalian brain to be “the ultimate term of complication and perfecting of the nervous system…”.

For Cajal, there are two especially conspicuous changes we see in nervous systems as we climb the phylogenetic ladder. We find: 1) aggregation of nerve tissue, as well as 2) increased complexity of peripheral processes. As an example of aggregation, he notes that the “double chain” of ladder-like ganglia running along the length of simple organisms (see the diagram from a couple posts back) is supplanted by our more familiar spinal cord — a single tube that runs along the midline. At first glance, this seems like a move in the direction of simplification and less complexity, but this is more apparent than real. The important thing, Cajal tells us, is that it’s a move toward a better and more efficient design; it does more work with less. As you move cell bodies toward the midline into a single compact structure (see figure below, contrasting right with left), you save on cabling by not having to extend long processes to the opposite side of the body. He later explains this basic principle as trying to create “the greatest possible number of associations with the shortest possible length of conductors.”

Another big general principle he notes (his first one, actually) is the multiplication of neurons and processes. Larger and more complex animals have more neurons, he says, because if they didn’t, they’d be sampling the world (sensory function) and actuating their bodies (motor function) with less precision. The nervous system’s “pixel size” would effectively increase (i.e. get worse) if the same 10 neurons went from having to represent a worm’s skin surface to an elephant’s skin surface.

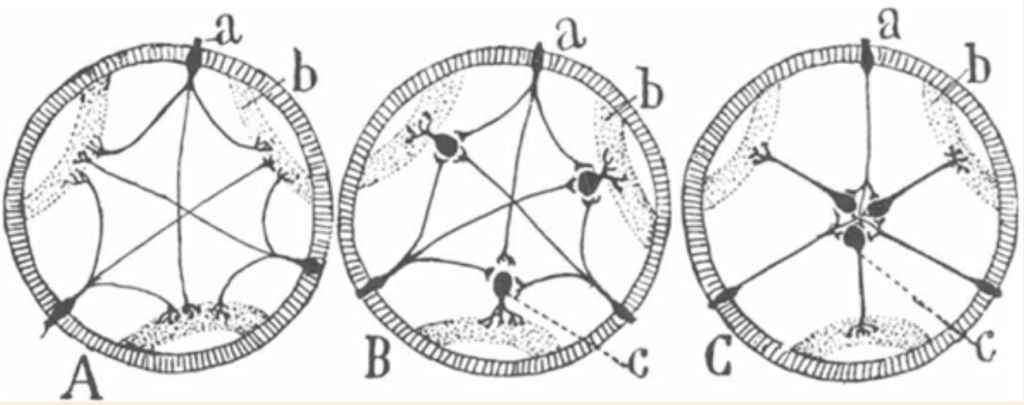

Cajal gives us a famous diagram (below) summarizing his ‘multiplication’ principle, which argues that increasing the number of neurons and packing them into ganglia helps save on the total amount of brain cabling. He makes his argument by sketching sensorimotor connections in cross-sections through a series of generic invertebrates.

In the animal on the left, there are three total neurons (labeled ‘a’), and each one has to extend three long branches to innervate all three muscles (labeled ‘b’). In the middle animal, we’ve doubled the number of neurons, adding a dedicated motor neuron to ‘actuate’ each of the three muscles. The real savings comes in the animal on the right, where, in addition to simply adding motor neurons, we also aggregate them centrally. We can now take advantage of a ‘hub-and spokes’ organization, where we achieve the same effective connectivity (all sensory neurons to all motor neurons) using much less cabling.

Leave a comment