Cajal ends big on chapter one of the Textura, with a meditation on how much of reality our brains can ultimately know. Reading this actually feels a bit like Descartes’ first meditation, where he keeps trying to take his own legs out from under him, philosophically, to see what he might have left to stand on. There’s nothing here modern post-‘Matrix’ ears will find edgy or scandalous, but it’s still really interesting to hear history’s most influential neuroscientist think out loud about human nature and biological destiny. Plus, it gives us a peek into Cajal’s philosophy of life, which is, unsurprisingly, very much knit up with his ideas about the brain.

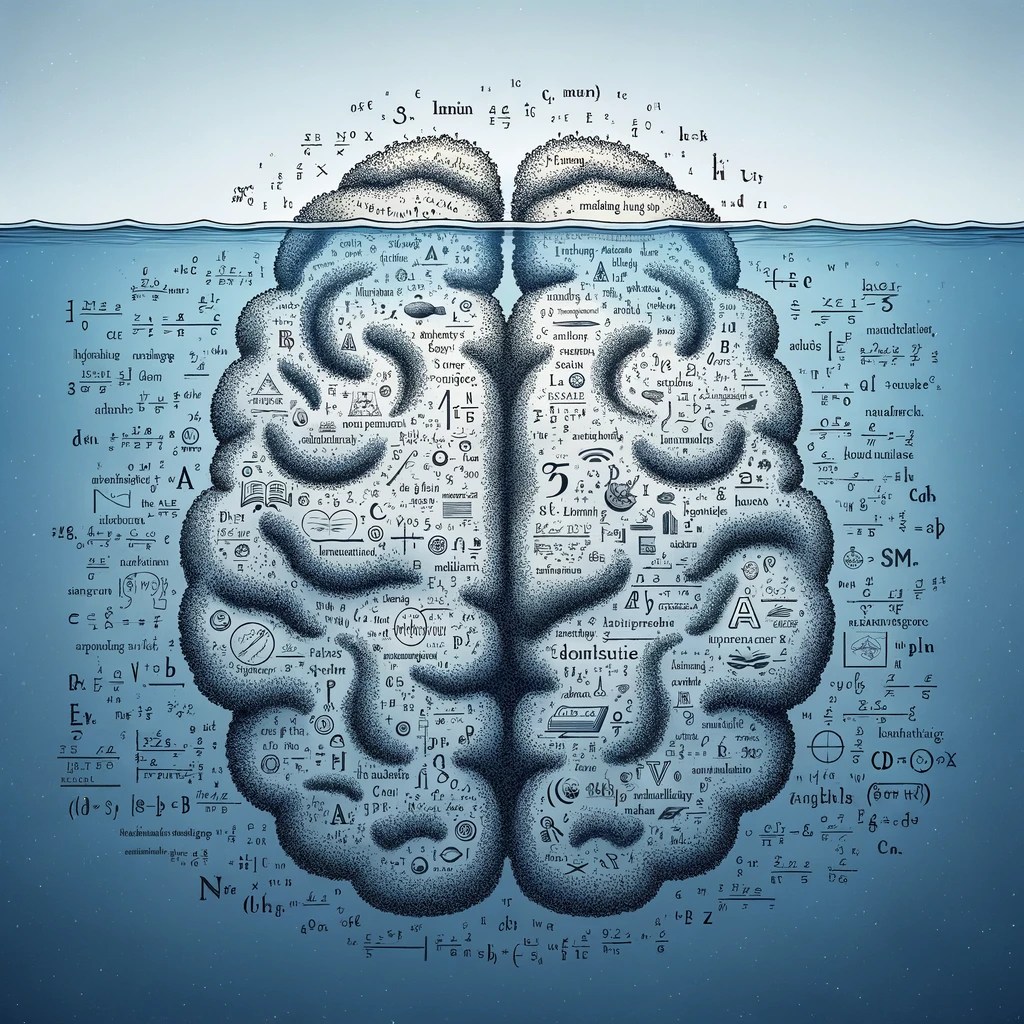

His first point is that our brains will always run up against a fundamental limit in their contemplation of reality. However much our brains may be elaborated and ‘perfected’ over time, the result is simply going to be a device that’s making more elaborate and more perfect approximations of and reactions to reality. We’ll never know matter itself — ‘the noumenon of Kant’, as Cajal tells it — only the effects it has on us.

But well before we run into that kind of ultimate philosophical/theoretical limit to knowledge, we have to face the more straightforwardly humbling fact that our sense organs are finite, and only ever capturing a small and limited portion of the world. All that we ever know, Cajal says, is “the effects that the vibrations of matter produce in the brain.” Damn.

Perhaps we can still hope that evolution might push us to a greater degree of perfection, so that our sampling/copying/responding to reality is getting better, and the world is truly being known more and better over time? Well, maybe to some extent, but before we get too hopeful, Cajal reminds us that evolution isn’t like some peepshow slowly raising the curtain of perceptual ignorance to reveal the pure reality hiding behind things. It’s more like the microscope’s system of mirrors and lenses that are used to add emphasis and to zoom in. There are perceptual exaggerations that enhance and sharpen, but also distortions one must acknowledge and deal with. Taking this back to the realm of the brain, Cajal accepts the notion that our nervous systems may, at any time, contain “aberrant intercellular connections” that are suited for the “present conditions of existence” much more than they are for ascertaining truth eternal. He even points to these aberrant connections being the seat of what he calls “secular errors”, among them, the belief in free will. “The true finality of our cerebral organization is not the knowledge of the true connections among the phenomena of the universe […] but the establishment of real or illusory connections among those phenomena which provide the best aid for the conservation of the individual and the species.” If our brains were philosophers, they’d be unsentimental pragmatists, not skyward-looking transcendentalists.

But Cajal being Cajal, he doesn’t turn this into a counsel of despair. He rallies. He urges us to see science as the noble way out of the prison of useful illusions biology has forged for us:

“The true spirit of philosophy and science is oriented to, and works for, the destruction of all these lay adaptations to errors, which may have been temporarily useful. We long, indeed for a happier time for the individual and the entire human kind when truth and usefulness will become one and the same thing.”

Maybe we never reach the heavens, but we can at least lift ourselves up.

Leave a comment