“And when once the possibility of some kind of mechanical interpretation is established, Mechanical Science, in her present mood, will not hesitate to set her brand of ownership upon the matter, feeling sure that it is only a question of time when the exact mechanical explanation of the case shall be found out.”

James, The Principles

Having left us with the broad metaphor of habits in the brain being like the channels furrowed out by rushing water, James next tries to get more specific. “[C]an we say just what mechanical facts the expression ‘change of habit’ covers when it is applied to a nervous system?”

The short answer is “not really,” at least in James’ time, and he doesn’t pretend otherwise. Today we have lots of mechanistic explanations for the phenomenon of sensory habituation — the fact that we get used to things with repetition — and most of these boil down to some kind of finite cellular resource being exhausted, or spent to its maximum. When a neuron delivers a little dollop of neurotransmitter to signal a downstream cell, for example, it starts to run out of neurotransmitter pretty quickly, and its relative influence starts to peter out. Ergo, habituation.

James, of course, knew none of these cellular specifics, but his account of a plausible mechanism is still really interesting, and vividly articulates the outlines of a research agenda for investigating habit, and brain plasticity more generally. Having acknowledged that he’s kind of pawing in the dark, he tells us that he’s going to frame “an abstract and general scheme of processes which the physical changes in question may be like.” This account of what things may be like, I’d venture, is still the basic mental scaffolding many neuroscientists have in mind when they think of plasticity.

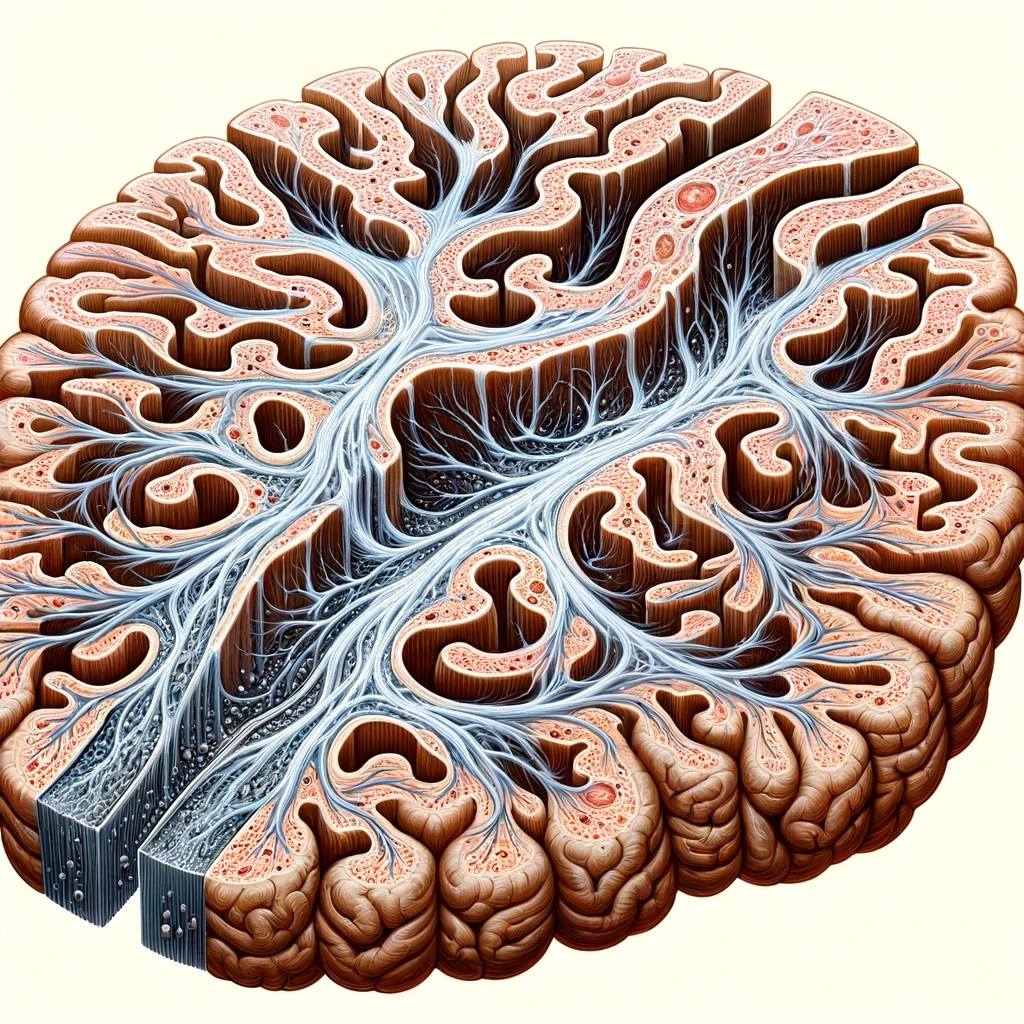

Recall the simple examples from the previous post describing what we might call ‘favorable molding through use’. A lock’s action gets smoother as the key is repeatedly inserted. A valley gets carved from rushing water. A sheet of paper ‘wants’ to fold along a crease. In all of these cases, there’s an “outward agent” (James’ term) that’s the providing the impetus for change (the key, the water, the act of creasing). What’s the outward agent of change in the brain? It can’t be mechanical, James tells us, because the world never actually lays its hands on our brains (unless something horrific has happened). Brains are floating in fluid, in the dark, and housed under a dense shelf of bone.

Instead, James notes, the agents of neural change are the rushing electrical currents that come streaming in from the senses. The language and imagery is admittedly a bit loosey-goosey by the standards of contemporary neuro, but the core idea holds up, and still gives pause: the brain’s pathways self-adjust in response to propagating electrical activity. They are not rigid, unyielding conduits for current, but rather are themselves affected by the currents they carry. More to the point, pathways (connections) are favored and retained in proportion to their relative use. “Use it or lose it” is the iron law of neuroplasticity, and James knew this back in the day, even if his concept of cellular-scale anatomy was super fuzzy. For purposes of historical interest (NOTE: This is wrong! ), James thought of the brain as something like a spongy medium through which electrical currents flowed and bored out channels by local molecular rearrangements. A few times he mentions the idea that any currents coming in (from the senses) have to find a way out, which lends a kind of inexorability to things. While it’s correct that if current flows in it has to also flow out, this isn’t a principle we apply in bulk to the entire brain to explain pathway formation. (End digression)

To recap and express things another way: we’ve arrived at the idea that habits become self-sustaining through a kind of positive feedback process involving an agent and a medium. At first there’s a trickle. That trickle effortfully scrapes out an initial shallow path, which the next trickle will sculpt, more easily, into a deeper path. And so on until that trickle is eventually a rushing stream in a bored-out valley. The water eventually has no choice but to follow its carved-out destiny, and our habit, for better or for worse, is fully established. That first cigarette has become our hundredth pack.

This is basically an evolutionary/incrementalist argument, and like all such arguments, it shows how iterating on some set of initial conditions can create unexpected degrees of influence or complexity. Lurking behind this is always the question, though, of how things got started in the first place. “[N]othing is easier than to imagine how, when a current once has traversed a path, it should traverse it more readily still a second time. But what made it ever traverse it the first time?” That slippery slope from the first cigarette to the hundredth makes sense, but what made us reach for the first one?

James’ answer? Chance. Elaborating on his currents-through-a-porous-sponge idea of the brain, he has us imagine that there are occasional and unpredictable ‘blockages’ that owe to “accidents of nutrition.” Because of this, a new path becomes accidentally favored, and then gets entrenched through repeated use. He admits that all of this is “vague to the last degree” but this can actually be seen as a virtue. He reasons in big themes and broad gestures, and these have to a large degree held up over time. The important moral of this story — bigger than particulars about blockages, rearrangements, currents, etc, which are definitely wrong in the details — is that there are both deterministic and random elements to how connections are laid down in the brain. We are creatures of habit, and our particular habits are creatures of chance.

So far, James hasn’t really made a special appeal to the fact that brains are (obviously) organic, and most of his examples imply a process where the physical substrate of habit formation involves something being incrementally removed or eroded with repeated use. This is helpful for initially grounding intuition, but it misses something critical: in living matter, things are constantly growing and being nourished. The brain isn’t just displaced by some outward agent, but instead “grows to the modes in which it has been exercised.” The brain meets the world halfway, and undergoes a process of “incessant nutritive renovation” that we can think of as fixing in place the impressions applied to it. Habit formation is a modification of growth, in other words, and this can account for the observation that practice often pays off only after some delay, and with a bit of rest. “[W]e learn to swim during the winter and to skate during the summer” as James tells us.

Leave a comment