Why do we have habits, and what are they good for?

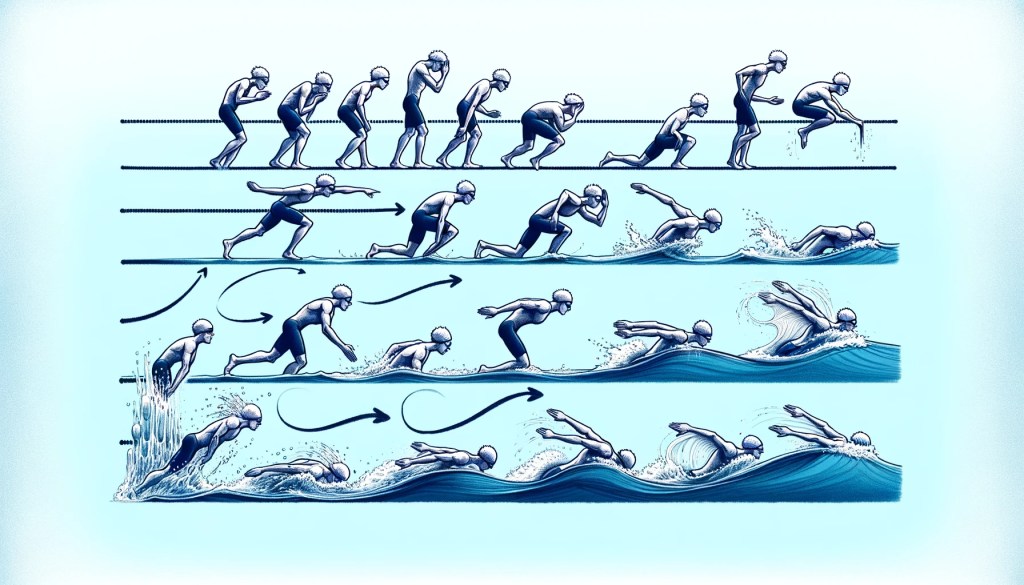

James has two answers. The first is that “habit simplifies the movements required to achieve a given result, makes them more accurate and diminishes fatigue.” In general, the more we can hand over to what James calls, quite poignantly, “the effortless custody of automatism”, the better. When you first learn to swim, you thrash your arms about mindlessly, and don’t have any concept of an organized ‘stroke’ with a distinct catch, pull, and glide. There’s just a series of mostly desperate and spastic contortions you go through that keep you afloat, and generally moving in one direction. You might be able to make it to the end of the pool doing this, but boy will you be stressed and exhausted.

A competitive swimmer, in striking contrast, looks like they’re doing some kind of graceful water yoga (see here — for nonswimmers: 59 seconds for very casually swum 100 meters is extremely impressive!). With a few elegant twists and flicks that they barely have to think about, they’re at the other end of the pool, their heartrate hardly above resting. They use their bodies with enormous efficiency, and habit is the means by which they’re transformed from an infant thrashing in the water to a human harpoon.

In a sense, habit is our superpower as a species. All animals enjoy its fruits, but we’re unique in having come to truly own it, channel it, and place it under the stewardship of slow, deliberate, intentional practice. A dog may become a better swimmer over time, but its improvements will always be incremental; an exploration of movements that are strictly adjacent to those endowed by nature. Humans, by contrast, pick up a whole new bodily language when they become great swimmers. There are nuances of glide and rotation that take years to pick up. As James describes it, “Man is born with a tendency to do more things than he has ready-made arrangements for in his nerve centres.” We push our nervous system’s habit-forming machinery into an extreme regime.

Sticking with our example of the swimmer, we can touch upon James’ second proposal for the benefit of habit: it “diminishes the conscious attention with which our acts are performed.” Learning to swim is not just physically exhausting, but mentally as well. There is an enormous amount to keep in mind as one goes through the sequence of movements involved in a stroke — a thousand micro-decisions and adjustments about when the arm should be relaxed, where to catch the water, how much to rotate the shoulders, how long to glide, when to kick relative to the pull. There are dozens of component movements, and probably an order magnitude more counterproductive movements that must be vetoed and suppressed. Learning all of this is challenging and effortful, but habit brings it about that “each event calls up its own appropriate successor without any alternative offering itself, and without any reference to the conscious will.” It takes an act of will (many of them, in fact!) to stitch together component movements into a single fluid gesture, but with enough practice, the final movement is virtually effortless, and “fused into a continuous stream.”

In James’ view, this turns us into machines of a sort, and we hear echoes here of his earlier thoughts on “starting-gun” style tasks that are reaction-time limited. You’ll recall that in the section on reaction time, he noted that it seems “as if it [the cue] started the reaction, by a sort of fatality, as if no psychic process of perception or volition had a chance to intervene.” A complex task is launched by a single starting cue.

So it is with habit, James says, in that our bodies gradually come to hand control over to the environment:

“When we are learning to walk, to ride, to swim, stake, fence, write, play, or sing, we interrupt ourselves at every step by unnecesary movements and false notes. When we are proficients, on the contrary, the results not only follow with the very minimum of muscular action requisite to bring them forth, they also follow from a single instantanous ‘cue’. The marksman sees the bird, and, before he knows it, he has aimed and shot.”

James leans hard into the ‘reflexological’ model of brain function to explain how this chaining together happens. In his view, every muscular contraction serves both a sensory and a motor role. It’s an ‘output’ and an observable act of the motor system, but this act is also felt, and to that extent can serve as sensory input and trigger for a downstream motor act. Movement begets sensation, which triggers another movement, which begets another sensation, which triggers yet another movement…. and so on. The swimmer’s feeling of their bent elbow is the cue for their opposite arm to extend.

The overall picture that emerges from this is a bit dualistic. There are mindless processes of sensorimotor discharge that just ‘go on’, in James’ view, but in the absence of any guidance and policing, their overall combination into complex behaviors is messy, redundant, and slow. The will and volition sit above all this quasi-magically, favoring some arrangements and discarding others, overall narrowing and tightening up the chains of influence that run through the body. It’s a dynamic process of testing and selection, which very much fits in with James’ overall philosophical leanings. I’ll follow up on the relation between volition and habit in the next post — it’s a really interesting set of questions, but this post is already getting a bit long.

Leave a comment