To what extent are we out “in front” of our actions, and involved in their selection, maintenance, and monitoring? Every so often, sometimes for weeks at a time, I get this unsettling awareness of how many of my behaviors are just kind of happening, with essentially no contribution from the little floaty “me” that daydreams, worries, and yearns. It’s not like I feel like I’m a prisoner in some machine acting contrary my intents. Rather, it’s more like a huge amount of behavior is essentially just taking care of itself, in a way that the floaty me, when it spontaneously decides to check in on things, generally finds un-worrisome and unobjectionable. “Well whaddya know… look what I just did. Interesting.” I’m not breathing, but rather breathing is happening. A question is replied to, and then I recognize that the reply came from me.

Complex behaviors acquired through training — those which we might call ‘performances’ — give us an occasion to think about how much we really own our actions. When a certain act has been trained to death, there’s a real question about where the locus of control lies. In their hundredth performance of “The Nutcracker”, is the dancer really dancing, or is the dance just being danced? That’s a sort of highbrow example, perhaps un-relatable for most of us, but there are lots of more mundane cases too. I remember reading books to my infant daughter, with animated play voices and all, and then being surprised at closing the book to find that I had been reading for minutes. I was in the room reading, but off doing other things in my head.

James is really interested in the question of how much we remain introspectively “online” during habitual, acquired behaviors. He sees great virtue in automatism, and is happy to let it explain a large part of human nature, but is also apprehensive about a “nothing but” worldview in which all behavior is, at base, automatic.

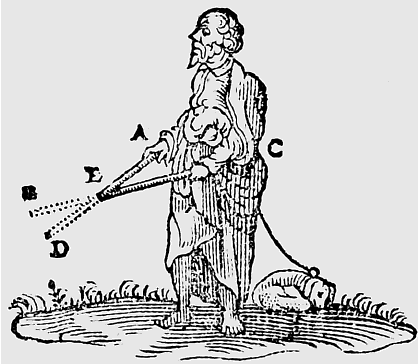

He finds a way into these issues by asking a bit more carefully about the intermediate ‘sensations’ that cue up the successive movements of a complex behavioral act. Recall that these are things like the swimmer’s feeling (sensation) of their high elbow prompting a reach (a motor act) of the opposite arm. He doesn’t see these sensations as distinct volitions (“now do this“), but rather as performing a kind of monitoring function. “The will, if any be present,” James says, referring to these intermediate sensations, “limits itself to a permission that they exert their motor effects.” In other words, these sensations are important for a surveillance-like function that’s looking for errors — deviations from the expected consequences behavior. These sensations don’t usually catch our attention, but when they result in a behavioral error, they give clues about how and where to correct course. You probably never think of all the little lip movements and mouthfeels that go into taking a sip of something, but if you’ve ever tried to drink your coffee after a shot of novocaine at the dentists, you immediately come to appreciate them. We have a “feeling of the proper management of the implement”, whether that implement is a musical instrument we’re holding, or our own lips.

Leave a comment