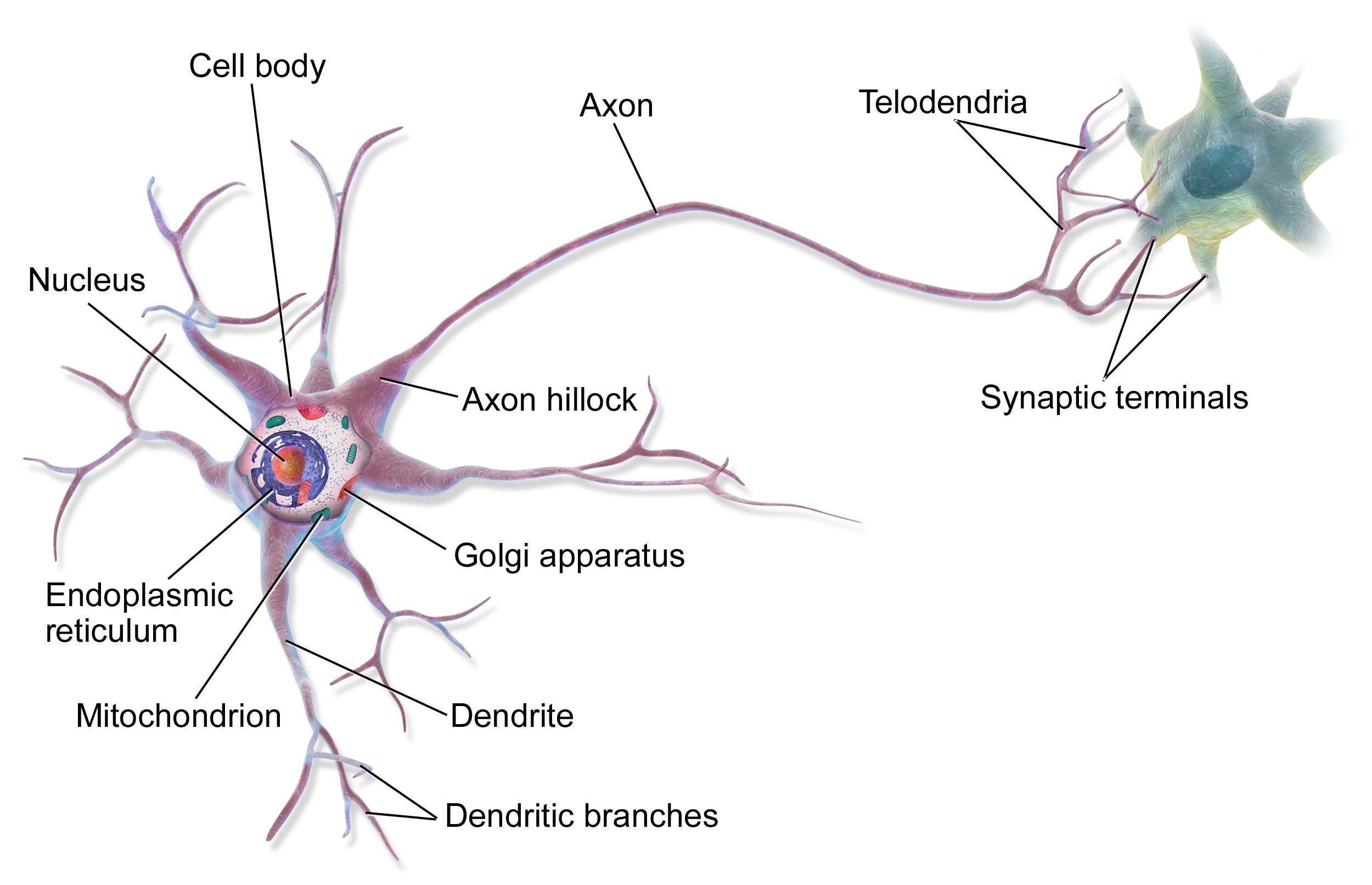

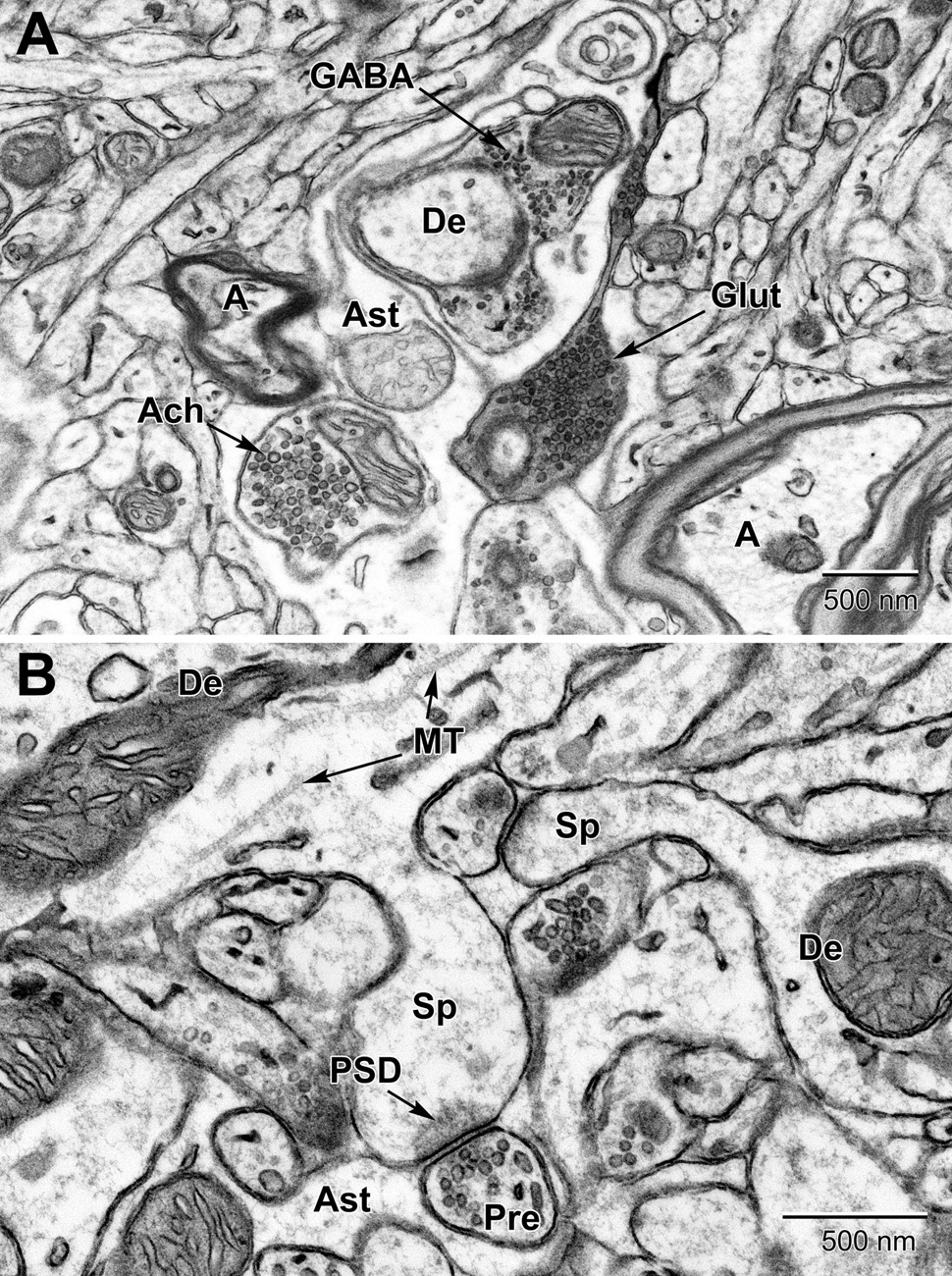

Cajal gives us a really evocative sense of what we’re up against as investigators of the brain. It’s a jungle, a nest of nests, a glorious and spectacular mess of wormy processes and crisscrossing fibers. In college textbooks you see cartoon neurons in isolation (like the one below, on the left), with their various protrusions textured in different color pastels and clearly labeled. In reality, there’s no free space in the brain. Everything writhes up against everything else, packed like the bodies of the damned in a renaissance painting. Cajal saw sorting this out as an intellectual puzzle, to be sure, but one senses that what really invigorated him was the larger poetic metaphor: a messy and seemingly impenetrable frontier that could be tamed through relentless investigation, and which slowly yielded its secrets to the heroic powers of inquiry.

Left: Cartoon neuron, courtesy of Wikipedia. Right: The real deal. Image of brain tissue obtained from an electron microscope. Described in this paper, by Nahirney and Tremblay (2021)

If you haven’t read much by Cajal before, you probably think this is romantic hyperbole, so here he is, describing things in his own words:

“Champolion, guessing the dead language of Egyptian hieroglyphics, and Layard and Rawlinson, revealing the mysterious meaning of cuneiform characters in the inscriptions in Nineveh and Babylon, have posed for themselves much simpler problems than the neurologists. Because the latter had to guess, with the help of ingenious methods, first the existence of similarly mysterious characters named cells (those laminations of unknowns, as Letamendi named the layers of pyramids in the cerebral cortex), and later to penetrate into the arcanum of their significance and functions.”

The passage is revealing, and it gives the essence of Cajal’s project. He was trying to tell a functional story about how the brain shuttled signals around between its cells, and he was also trying to establish that these cells even existed in the first place. In science (and I guess life, really), one often finds themselves in this curious predicament where there’s some hypothesized entity (like the brain cell, for Cajal) that’s hard to observe directly, but which can be guessed at or inferred by virtue of how it behaves, or by the theoretical and explanatory advantages it confers. What a thing is and what a thing does are questions that can be very messily tied together sometimes.

As a ‘neuronist’, Cajal believed (correctly) that the brain was made up of a huge number of individual cells, which were organized into circuits that enforced a specific logic and directionality to information flow. His scientific adversaries (and man, did he really loathe them!) were the so-called ‘reticularists’, who believed that the brain was really the tangled mesh it appeared to be — a contiguous network of fibers with no discrete units. The reticularists were objectively wrong (the brain is made of cells, period), but perhaps metaphorically correct in seeking models that cast brain function in terms of collective and distributed activity.

Cajal tells the neuronists vs. reticularists story beautifully in the second chapter of the Textura, through the lens of method. He walks us through different techniques for interrogating brain tissue, showing how each enabled a new kind of glimpse, or lent a new perspective. We see the neuron slowly come into focus, over decades, becoming better known and less ambiguous, its processes beginning to stand in sharp relief against the surrounding tissue.

Cajal has a palpable zeal for taxonomies, and gives us a few ways of thinking about the nervous system’s fundamental elements. The cast of cellular characters, he tells us, can be thought of as comprising three basic types: 1) nerve cells, 2) neuroglial cells, and 3) epithelial (or ependymal) cells. More macroscopically, these elements tend to be organized in a few different kinds of structural motifs: 1) neural centers like the cerebrospinal axis, and the sensory and sympathetic ganglia, 2) nerves (bundles of axons — the long processes that extend from single cells), and 3) peripheral terminations (nerve endings connecting up with muscles, glands, and the sense organs). The last of these — the peripheral processes — were the first to be understood clearly because they were the most experimentally accessible, and also the least anatomically complex (in relative terms, of course).

Why is the central nervous system (i.e. the brain and spinal cord) such a mess, and so difficult to study? Well, how much time do you have, Cajal asks. For starters, its neurons have a stellate (star-like) shape, with gossamer fibers that can extend for hundreds of times the length of the cell body. Also, these processes are soft, and prone to tearing when you try to dissect them. And to top it off, they have very little natural contrast against the surrounding neuropil, making them about as easy to spot as a crow at night. “It can be predicted,” Cajal declares, “with no risk of falling into exaggeration, that the perfect completion of the Neurology edifice will demand yet the labor of many centuries.” This one did turn out to be hyperbole, it seems. Cajal died in 1934, and already in 2024 — less than a century later — we have a spectacularly detailed map (a ‘census’, of sorts) of the brain’s basic cell types and connections. Surely there’s more work to be done before we have a complete cellular brain map on hand, and prediction is a fool’s game, but I’d be surprised if we haven’t fully realized Cajal’s vision in another 50 years.

The plan for the next few posts is to take one anatomical method per post (for the most part), and give a tour of what each method revealed, as well as some of the disputes it engendered (at least, in Cajal’s view). We will also encounter some tragic figures and colorful personalities along the way. See you soon!

Leave a comment